At Science World, we're committed to celebrating diverse, brilliant scientific minds and their contributions to science, technology, engineering, arts and design, and mathematics (STEAM).

From life-changing discoveries to groundbreaking technologies, countless women in Canada have changed the course of history for the better and are making history as we speak with their scientific accomplishments.

This celebratory list of names is just some of the women who've disrupted norms and set precedents in their field.

Dr. Cynthia Breazeal

What are the long-term impacts of living with artificial intelligence (AI)? As a pioneer of social robotics and human robot interaction, Dr. Breazeal’s research focuses on this question. She explores how robots can be designed to promote humanity’s best interest: relationship building, health and wellness, and education. Her mission: to “democratize” AI. Whether that’s children as young as kindergarten or high school graduates, Dr. Breazeal believes these technologies should be accessible to all, especially our youngest minds.

Dr. Hayat Sindi

As a biotechnologist, Dr. Sindi explores the connection between science and social impact. As Co-Founder of Diagnostics For All, she supports communities with major barriers to healthcare in receiving life-saving medical results through a point-of-care diagnostic device that helps identify any injury, condition or disease. Through her organization, Dr. Sindi is ensuring that everyone has access to inexpensive forms of diagnosis, especially where access to power, water or trained doctors are limited. She is also passionate about encouraging imagination and ingenuity for Muslim youth who are looking to pursue science, technology and engineering.

Juliana Rotich

Imagine being able to connect to the internet even from the most remote areas in the world or being able to crowdsource information happening right in your neighbourhood? As a technologist, Juliana is doing both and her groundbreaking efforts to make data more accessible is getting even the most barriered demographics connected to the digital economy. She co-founded BRCK which provides fast, reliable and free internet in Kenya. Through a self-powered mobile WiFi router users can access a free public WiFi network to connect to the internet. Her non-profit Ushahidi, provides crowdsourcing software and services to help the communication gap between communities and government bodies. These technologies help communities aggregate information to bring global attention to their issues and use evidence-based techniques to keep governments accountable.

Mae Jemison

Growing up in Chicago, Mae Jemison watched Star Trek and dreamed of going into space. She credits Nichelle Nichols' portrayal of Lieutenant Uhura as enabling her to envision a Black woman astronaut. Entering Stanford University at the young age of 16, Jemison studied medicine and served as a physician in the Peace Corps. In 1987, she successfully applied to NASA’s astronaut training program. Dr. Mae Jemison made history on September 12, 1992 as the first Black woman to travel into space. Serving as a mission specialist, Jemison and the STS-47 crew orbited the Earth for almost 8 days, conducting microgravity investigations in materials and life sciences. She began each shift with the communication, “Hailing frequencies open,” a line from Star Trek made famous by Lieutenant Uhuara. Today, Dr. Jemison leads a global initiative to ensure the capabilities for human travel beyond our solar system within 100 years.

Gladys West

Next time you hear, “Keep left at the fork,” thank Gladys West. The Global Positioning System (GPS) is one of the most ubiquitous technologies of our time, and its uses stretch far beyond getting from point A to point B. Today, we recognize Gladys West for her role in revolutionizing geodesy—the science of measuring the Earth’s shape, orientation in space and gravitational field. West joined the Naval Surface Warfare Center in Virginia in the 1960s as a computer programmer. At that time, precise measurements of the Earth—an imperfect sphere—didn’t exist. Using satellite information, West developed increasingly complex mathematical models that took into account our planet’s variations in sea level. In the 1980s, she herself programmed the IBM 7030 Stretch computer with algorithms that accounted for how gravitational and tidal forces distort the Earth’s shape. The program modelled the shape of the earth (the geoid) in the greatest detail to date. West’s model was essential to the development of the Global Positioning System.

Tu Youyou

In the late 1960s, during the Vietnam War, malaria epidemics had devastating impacts on military, at times disabling up to 90% of troops. The North Vietnamese and Chinese governments enlisted the help of nearly 600 scientists to conduct secret malaria research— codenamed Project 523. For 3 years, chemist Tu Youyou led a team that observed the disease’s destruction. She came up with the idea to investigate ancient Chinese texts for traditional uses of herbal medicine. By herself, she traveled around China, gaining knowledge from practitioners. In the end, it was the combination of two texts that helped her develop a treatment. First, a 1,600-year-old recipe that used sweet wormwood to treat fevers. Then, an effective extraction method from a 340 AD text by Ge Hong, The Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergency Treatments. This allowed scientists to isolate the pure active compound now known as qinghaosu (in English, artemisinin). Tu Youyou insisted on testing the medicine herself first to make sure it was safe. In 2015, she was awarded with the Nobel Prize in Medicine for her work in saving millions of lives around the world.

Chien-Shiung Wu

Prior to the invention of particle accelerators—wherein subatomic particles are smashed into each other at high speeds— physicists had accepted a theory known as the conservation of parity. It stated that the result of an experiment would remain the same if all the parts were replaced by their mirror images — which is exactly what we see for large-scale objects like baseballs and planets. However, in the 1950s, a newly discovered subatomic particle seemed to violate conservation of parity. The K meson, while identical in every other way, appeared to have 2 “mirror image” versions that decayed differently. Chinese American physicist Chien-Shiung Wu devised and conducted the Wu Experiment, which shook the world of physics. Its groundbreaking results found that parity of conservation could no longer be assumed in all cases. The results also solved the Ozma problem — giving a scientific definition of left and right without reference to the human body. The physicists who originated the idea of parity nonconservation received the Nobel Prize in physics in 1957, while Chien-Shiung Wu was not publicly recognized for her role until 1978. Today, she is seen as a significant contributor to the field of nuclear physics.

Rosalind Franklin

Photo 51 — taken in 1952 at King’s College in London under the supervision of Dr. Rosalind Franklin — is considered one of the most important photographs ever taken. James Watson describes the moment he first saw it: “My mouth fell open and my pulse began to race.” The X-ray diffraction image of DNA revealed a pattern that confirmed the helix structure predicted by Watson and Crick. This gave rise to modern molecular biology as we know it. Rosalind Franklin also holds a prominent place in the history of virology — her X-ray diffraction pictures of crystallized viruses revealed their structure. Today, researchers use these tools to investigate viruses. The inscription on her gravestone reads, “Scientist: her work on viruses was of lasting benefit to mankind.”

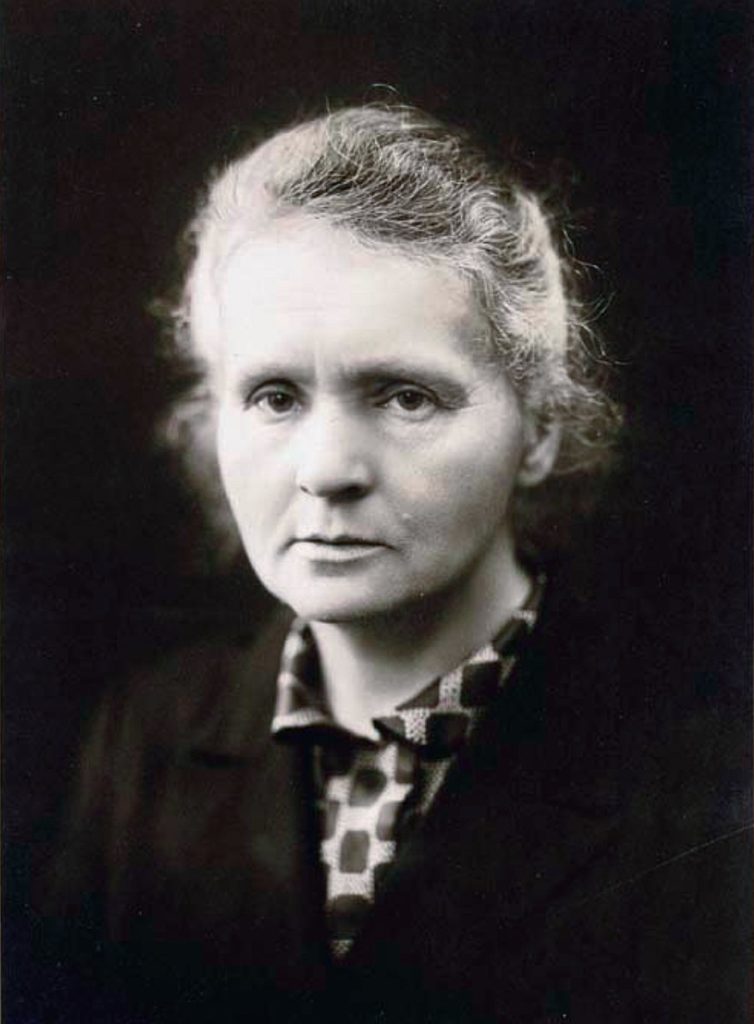

Marie Curie

The first university classes Marie Curie ever attended were illegal. In 1885, the Russian Empire controlled Poland and prohibited women from receiving higher education. So, Curie studied at the underground Flying University — a secret school taught in private homes where women could learn science. And the world is better for it. While investigating the properties of uranium, she discovered the phenomenon she named “radioactivity,” demonstrating that atoms can be broken and creating the field of atomic physics. With her husband, she discovered two new elements (radium and polonium). She significantly advanced the use of radiation in medicine, paving the way for cancer treatments still used today. The first woman to win a Nobel Prize, she is also the only woman to receive two Nobel Prizes in two scientific categories — physics and chemistry.

Émilie du Châtelet

Born into 18th century French aristocracy, Émilie du Châtelet’s love for science was sparked by scientists and mathematicians who visited her father’s weekly salon. At the time, Newton's Laws of Motion, which explain how forces and motion work, were still new and somewhat controversial. By the time Émilie du Châtelet was 12, she studied math and physics daily and spoke 5 languages. Her passion paid off. Her 1740 book Institutions de Physique was an important summary of the contemporary theories of physics. And before her early death in 1749, she completed the French translation of Newton’s Principia Mathematica (with her own derivation of the notion of conservation of energy) that helped legitimize Newton's theories in France. Today, her work is still the standard French translation.

Feeling inspired?

Keep it going! Our new exhibition, Trailblazing — Women in Canada since 1867, presented by Acuitas Therapeutics, invites visitors to celebrate 150 years of women's history in Canada.