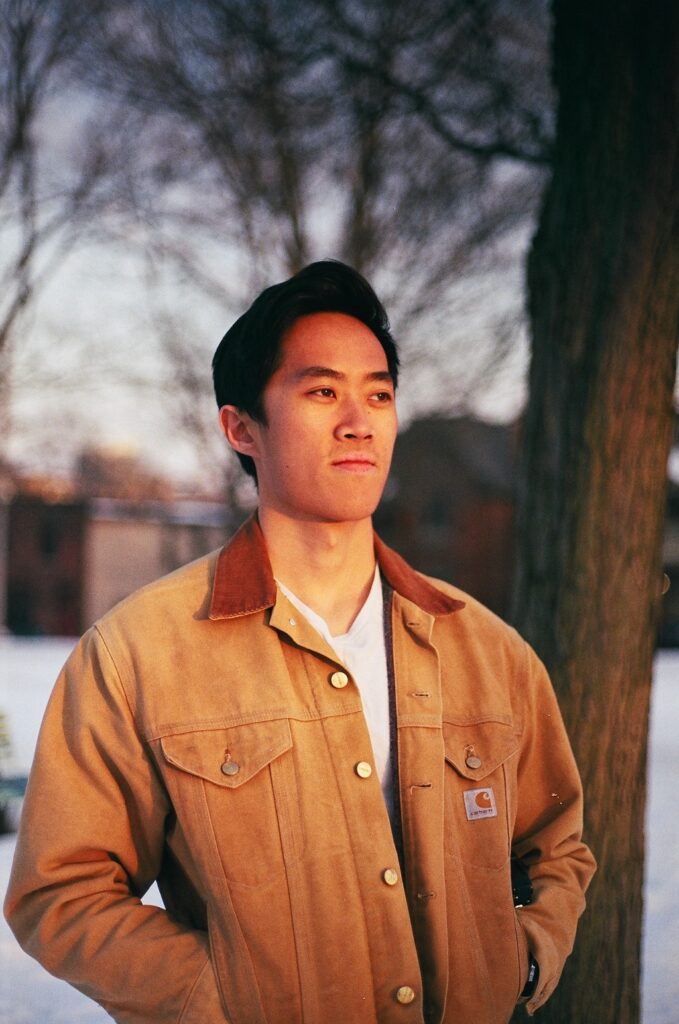

Guest post by Auston Chhor, a biologist at Raincoast Conservation Foundation and freelance writer, in celebration of Asian Heritage Month with Science World.

I remember the first day I called myself a biologist. I’d landed a job in Vancouver and was ready to start my new life wrestling fish and analyzing data.

My backstory couldn't have been more different from my coworkers’—I grew up in a suburb of Toronto, didn’t know how to camp, and had never seen a Pacific Salmon outside of a sushi restaurant. My childhood summers were spent playing Pokemon, and the question, “What do you want to do when you grow up?” had always induced a bit of anxiety in me.

By my senior year I still hadn’t decided what I wanted to do, and I was surrounded by ambitious, high-achieving peers—the perfect combination for an insecure 17-year-old. I was at the university fair with a friend when he announced that he was going to study marine biology.

I remember thinking, “Hold on. Are we even allowed to study that? Wasn’t this career path reserved for people who grew up by the coast and volunteered at dolphin rescue centres?"

We spent the rest of the day talking to schools with biology programs and as soon as I got home, I applied to every single one I could find.

I was always interested in the environment. I sorted through recycling with my school’s eco-club, religiously brought a re-useable water bottle to class, and binge-watched Planet Earth every snow day.

So, why did a career as a biologist feel so foreign to me?

Maybe it’s because I hardly ever saw a host on Animal Planet who looked like me, nor could I think of an environmentalist-of-colour with the same household-name status as Jane Goodall, Jacques Cousteau, or David Attenborough.

People of colour have historically been missing from the western environmental movement — likely due to its roots in white saviourism — resulting in a landscape today where it is difficult for those wanting to participate to feel like they belong.

An analysis of North American environmental organizations showed that while ethnic minorities comprise about 38% of the general population, only 16% of staff and 12% of upper management identified as minorities. The report also noted that only the Diversity Manager position was more likely to be held by people of colour, and few organizations had such a position at all.

Is it possible that racialized people are simply not as interested in studying the natural world? Unlikely. Surveys show that racialized people are more concerned than average about environmental issues such as climate change, possibly because they’re more likely to feel their negative impacts.

In my experience, I just couldn’t picture myself in the field. In the U.S., only 9% of fisheries scientists, 11% of forestry scientists, and 7% of birders identify as ethnic minorities. When Reuters published a list of the 1000 “most influential” climate scientists in the world, less than a quarter were from the global south. I found it much easier to picture myself being a doctor, engineer, or software designer, all career paths that were well-represented by people I could identify with.

Once I started job hunting, I found myself doubting my chances with organizations that don’t have a diverse team, and hating the feeling that I must be a trailblazer just to apply.

Another barrier, a sentiment that seems to be unique to the conservation sector, is the expectation that applicants should have conservation-focused experience in their personal lives.

While commendable, these requirements have likely fuelled the endless stream of pay-for-work internships that advertise experiences like helping elephants in Thailand or restoring a coral reef in The Seychelles.

Ethical concerns of “voluntourism” aside, these programs are inherently exclusive, reserved for those who can fork up their astronomical costs and are able to take time away from work, school, or family.

How did it work out for me? When my friend—of Vietnamese-Canadian heritage—told me of his goal to become a marine biologist, put simply, it made me feel like I could do it too. Seeing my friend have the courage to go against the status quo and pursue his interests empowered me to do the same, and this dynamic is something that we need to encourage more of.

Months after the university fair I was accepted into a biology program and, after I graduated, I pursued a master’s of science in fisheries.

Now, I work at Raincoast Conservation Foundation, helping tackle the myriad of issues facing wild Pacific salmon on the BC coast.

Hashtags such as #BlackInNature have highlighted the interest around improving the visibility of minorities in environmental work, and grants geared towards underrepresented groups will continue to play an important role in improving the accessibility of the field to all.

The current ecological crisis is affecting us all — some, more than others — so it’s absolutely essential that everyone gets to contribute to solving it.

Celebrate Asian Heritage Month!

From building airplanes in Chinatown, to conserving wild salmon in the Pacific, to breaking boundaries in Punjabi drag culture, to exploring the human virome, these experts are making history in STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art & design, and math).